dw:

when did we replace the word “said” with “was like”

When it occured to us that “said” implies a direct quote, while “was like” clarifies that you mean to communicate the person’s tone and general point without quoting them word for word.

THANK YOU

because I’m both a smart alec and a linguistics nerd, I’m going to add that the answer is sometime before 1982, which is the OED’s earliest citation for the phrase. Given how long it takes for slang to make it to formally attested sources – or perhaps I should say how long it did take before the internet was widespread, given how much that’s changed how we can access new usages as they’re developing – I’m gonna say at least the 1970s. It was apparently, at the time, stereotypically associated with valley girls, because the first attestation is in a song called “Valley Girl”.

By the way, the idea of having a word that implies a direct quote and one that implies an indirect quotation isn’t new – the older usage is “goes”. Like, “I told him I was angry, and he went [making exaggerated facial expression] ‘whaaat? why?’” This usage, apparently, can be traced back to Dickens.

So, really, we’re replacing ‘went’ with ‘was like’, not ‘said’.

for those of you who want more information about this, there’s an Actual Published Linguistics Paper here (you can read it there or download the pdf) about vernacular like. it turns out there are at least four uses of vernacular like, and only the quotative like can plausibly be traced back to valley girls in the 1980s; the other three uses (approximation, discourse marker, and particle) are at least a century older than that

Tag: linguistics nerd

Some of my favourite linguistic developments

‘Is that a thing?’ for ‘does that exist?’

Deliberate omission of grammar to show e.g. defeatedness, bewilderment, fury. As seen in Tumblr’s ‘what is this I don’t even’.

‘Because [noun]’. As in ‘we couldn’t have our picnic in the meadow because wasps.’

Use of kerning to indicate strong bewilderment, i.e. double-spaced letters usually denoting ‘what is happening?’ This one is really interesting because it doesn’t really translate well to speech. It’s something people have come up with that uses the medium of text over the internet as a new way of communicating instead of just a transcript of speech or a quicker way to send postal letters.

Just the general playing around with sentence structure and still being able to be understood. One of my favourites of these is the ‘subject: *verbs* / object: *is verb*’ couplet, as in:

Beekeeper: *keeps bees*

Bees: *is keep*or

Me: *holds puppy*

Puppy: *is hold*I just love how this all develops organically with no deciding body, and how we all understand and adapt to it.

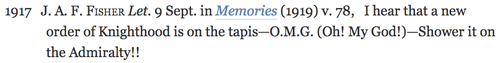

today i learned that the first use of “omg" occurred in 1917 in a letter to winston fucking churchill

in case you think im fucking with you:

I see this “fact” all the time, but folks, this is actually a JOKE THIS GUY IS MAKING. He’s not using an excited acronym, he’s making FUN of the service. In the Order of St. Michael and St. George (honours given to colonial servants), you can be a Companion, a Knight Commander or a Knight Grand Cross, which were abbreviated to CMG, KCMG and KGCMG. The joke is they’re so up themselves that it stands for “Call Me God”, “Kindly Call Me God”, and “God Calls Me God”. “O.M.G./Oh My God” would be another meaningless award for people to be smug about.

tl;dr: O.M.G. in 1919 is a JOKE not an exclamation. Let us all not confuse the timeline of language innovation and make fun of colonial bullshit instead.

my dad keeps asking why grammatical gender isn’t sexist and I just

idk what to say to this, like words directly relating to people should be able to be made gender neutral, I can see wanting that, but like…grammatical gender is usually just a tool for declensions and word agreement

am I wrong like reply what you think too so I can get a coherent argument

I hate when my parents try to start political arguments with me it’s so stressful and they always expect me to respond and debate immediately? I don’t want to debate my parents

because it has nothing to do with systemic oppression of women, except in some instances when it applies to people, but that also exists in a mostly non gendered language like english. come to think of it, do native speakers of languages with grammatical gender think of these words as gendered? or is it more a tool for non native speakers trying to learn them? even in latin you can’t really divide the declensions based on gender alone since there are always exceptions, like agricola, nauta, etc. in 1st and the feminine 2nd declension tree nouns. it’s about the common inflections more than gender.

I’m sorry, I don’t have sources and I’m too busy to google.

But I have read in the past that cultures with gendered languages are generally more sexist than countries with gender neutral languages. I don’t know. It makes sense to me. The languages we learn have an incredible impact on the way we think. I’ve read some fascinating articles about the way language affects how we think. And to have the entire world broken down in male and female (and sometimes neither) I don’t know, it makes sense to me.

I had also read a think talking about how gendered language affects how people view and describe objects. I think they compared Italian and German? In one language, the word “bridge” is feminine, and in the other, it is masculine. When people were asked to describe the qualities of a bridge, they used different kinds of words. People for whom the word “bridge” was masculine would use traditionally “masculine” traits to describe it, like powerful, strong, etc, and people for whom is was feminine would use traditionally feminine traits, like supportive, etc.

That kind of thing.

Language shapes our thoughts. It’s so incredibly important. I think things like gendered grammar absolutely have an effect.

idk, those studies can get a bit over-simplified though…i mean, in latin, the word for manliness, “virtus,” is a feminine noun. actually, same thing with ancient greek “andreia.” it’s because abstract nouns happen to have that ending. sailor, farmer, and poet are feminine in latin. farmer was one of the highest lauded professions by conservative romans like cato the elder. demokratia and respublica are feminine, yet no women were full citizens.

Actually, nauta, agricola, and poeta (along with incola, auriga, pirata, or even Catilina, and a host of other 1st declension nouns that refer to people/professions the Romans regarded as male) are absolutely not feminine; they’re masculine. (The mnemonic is that they are PAIN nouns, because it’s a pain to remember that they take masculine agreement). bonus agricola, ‘the good farmer’, not *bona agricola.

Anthony Corbeill just published a book (Sexing the World) on how Latin’s grammatical gender affected Romans’ thinking etc. that I am DYING to get my hands on. (Maybe today is the day to give in and buy it on Amazon…)

oh, whoops, i meant that they are in 1st declension, which is primarily feminine. facepalm.

The ‘bridge’ study is probably this one. For what it’s worth, last time I read it, I did not sit there thinking ‘meh, this feels like over-simplified bullshit’. But the idea that language isn’t sexist because sometimes there are ‘good’ concepts with feminine nouns seems, with all due respect, to be possibly a bit simplistic. It’s not the case that sexist language requires all ‘feminine’ words to be negative, and all ‘male’ words to be positive. The Boroditsky, Schmidt & Phillips chapter certainly isn’t arguing that; it’s to do with what other concepts which we traditionally gender we then bring to bear on a gendered word: if it’s feminine it’s small, dainty, pretty; if it’s masculine it’s big, strong, durable. In and of itself this would probably just be an interesting quirk of language, but given that these are also concepts we apply to people, it’s easy to see how such usage is part of a far larger, more problematic system. Whether it’s just one more visible sign of that system, or whether it actively contributes to it might be another matter (I would argue that it would probably be dependent on the word – it’s easy to see how words relating to certain professions being heavily gendered one way or another might be problematic…)

Of course I thought of my sister. XD

“Let’s face it – English is a crazy language. There is no egg in eggplant nor ham in hamburger; neither apple nor pine in pineapple. English muffins weren’t invented in England or French fries in France. Sweetmeats are candies while sweetbreads, which aren’t sweet, are meat. We take English for granted. But if we explore its paradoxes, we find that quicksand can work slowly, boxing rings are square and a guinea pig is neither from Guinea nor is it a pig. And why is it that writers write but fingers don’t fing, grocers don’t groce and hammers don’t ham? If the plural of tooth is teeth, why isn’t the plural of booth beeth? One goose, 2 geese. So one moose, 2 meese? One index, 2 indices? Doesn’t it seem crazy that you can make amends but not one amend? If you have a bunch of odds and ends and get rid of all but one of them, what do you call it? If teachers taught, why didn’t preachers praught? If a vegetarian eats vegetables, what does a humanitarian eat? In what language do people recite at a play and play at a recital? Ship by truck and send cargo by ship? Have noses that run and feet that smell? How can a slim chance and a fat chance be the same, while a wise man and a wise guy are opposites? You have to marvel at the unique lunacy of a language in which your house can burn up as it burns down, in which you fill in a form by filling it out and in which an alarm goes off by going on. English was invented by people, not computers, and it reflects the creativity of the human race (which, of course, isn’t a race at all). That is why, when the stars are out, they are visible, but when the lights are out, they are invisible.”— (via be-killed)

But, but, but!

But, no, because there are reasons for all of those seemingly weird English bits.

Like “eggplant” is called “eggplant” because the white-skinned variety (to which the name originally applied) looks very egg-like.

The “hamburger” is named after the city of Hamburg.

The name “pineapple” originally (in Middle English) applied to pine cones (ie. the fruit of pines – the word “apple” at the time often being used more generically than it is now), and because the tropical pineapple bears a strong resemblance to pine cones, the name transferred.

The “English” muffin was not invented in England, no, but it was invented by an Englishman, Samuel Bath Thomas, in New York in 1894. The name differentiates the “English-style” savoury muffin from “American” muffins which are commonly sweet.

“French fries” are not named for their country of origin (also the United States), but for their preparation. They are French-cut fried potatoes – ie. French fries.

“Sweetmeats” originally referred to candied fruits or nuts, and given that we still use the term “nutmeat” to describe the edible part of a nut and “flesh” to describe the edible part of a fruit, that makes sense.

“Sweetbread” has nothing whatsoever to do with bread, but comes from the Middle English “brede”, meaning “roasted meat”. “Sweet” refers not to being sugary, but to being rich in flavour.

Similarly, “quicksand” means not “fast sand”, but “living sand” (from the Old English “cwicu” – “alive”).

The term boxing “ring” is a holdover from the time when the “ring” would have been just that – a circle marked on the ground. The first square boxing ring did not appear until 1838. In the rules of the sport itself, there is also a ring – real or imagined – drawn within the now square arena in which the boxers meet at the beginning of each round.

The etymology of “guinea pig” is disputed, but one suggestion has been that the sounds the animals makes are similar to the grunting of a pig. Also, as with the “apple” that caused confusion in “pineapple”, “Guinea” used to be the catch-all name for any unspecified far away place. Another suggestion is that the animal was named after the sailors – the “Guinea-men” – who first brought it to England from its native South America.

As for the discrepancies between verb and noun forms, between plurals, and conjugations, these are always the result of differing word derivation.

Writers write because the meaning of the word “writer” is “one who writes”, but fingers never fing because “finger” is not a noun derived from a verb. Hammers don’t ham because the noun “hammer”, derived from the Old Norse “hamarr”, meaning “stone” and/or “tool with a stone head”, is how we derive the verb “to hammer” – ie. to use such a tool. But grocers, in a certain sense, DO “groce”, given that the word “grocer” means “one who buys and sells in gross” (from the Latin “grossarius”, meaning “wholesaler”).

“Tooth” and “teeth” is the legacy of the Old English “toð” and “teð”, whereas “booth” comes from the Old Danish “boþ”. “Goose” and “geese”, from the Old English “gōs” and “gēs”, follow the same pattern, but “moose” is an Algonquian word (Abenaki: “moz”, Ojibwe: “mooz”, Delaware: “mo:s”). “Index” is a Latin loanword, and forms its plural quite predictably by the Latin model (ex: matrix -> matrices, vertex -> vertices, helix -> helices).

One can “make amends” – which is to say, to amend what needs amending – and, case by case, can “amend” or “make an amendment”. No conflict there.

“Odds and ends” is not word, but a phrase. It is, necessarily, by its very meaning, plural, given that it refers to a collection of miscellany. A single object can’t be described in the same terms as a group.

“Teach” and “taught” go back to Old English “tæcan” and “tæhte”, but “preach” comes from Latin “predician” (“præ” + “dicare” – “to proclaim”).

“Vegetarian” comes of “vegetable” and “agrarian” – put into common use in 1847 by the Vegetarian Society in Britain.

“Humanitarian”, on the other hand, is a portmanteau of “humanity” and “Unitarian”, coined in 1794 to described a Christian philosophical position – “One who affirms the humanity of Christ but denies his pre-existence and divinity”. It didn’t take on its current meaning of “ethical benevolence” until 1838. The meaning of “philanthropist” or “one who advocates or practices human action to solve social problems” didn’t come into use until 1842.

We recite a play because the word comes from the Latin “recitare” – “to read aloud, to repeat from memory”. “Recital” is “the act of reciting”. Even this usage makes sense if you consider that the Latin “cite” comes from the Greek “cieo” – “to move, to stir, to rouse , to excite, to call upon, to summon”. Music “rouses” an emotional response. One plays at a recital for an audience one has “called upon” to listen.

The verb “to ship” is obviously a holdover from when the primary means of moving goods was by ship, but “cargo” comes from the Spanish “cargar”, meaning “to load, to burden, to impose taxes”, via the Latin “carricare” – “to load on a cart”.

“Run” (moving fast) and “run” (flowing) are homonyms with different roots in Old English: “ærnan” – “to ride, to reach, to run to, to gain by running”, and “rinnan” – “to flow, to run together”. Noses flow in the second sense, while feet run in the first. Simillarly, “to smell” has both the meaning “to emit” or “to perceive” odor. Feet, naturally, may do the former, but not the latter.

“Fat chance” is an intentionally sarcastic expression of the sentiment “slim chance” in the same way that “Yeah, right” expresses doubt – by saying the opposite.

“Wise guy” vs. “wise man” is a result of two different uses of the word “wise”. Originally, from Old English “wis”, it meant “to know, to see”. It is closely related to Old English “wit” – “knowledge, understanding, intelligence, mind”. From German, we get “Witz”, meaning “joke, witticism”. So, a wise man knows, sees, and understands. A wise guy cracks jokes.

The seemingly contradictory “burn up” and “burn down” aren’t really contradictory at all, but relative. A thing which burns up is consumed by fire. A house burns down because, as it burns, it collapses.

“Fill in” and “fill out” are phrasal verbs with a difference of meaning so slight as to be largely interchangeable, but there is a difference of meaning. To use the example in the post, you fill OUT a form by filling it IN, not the other way around. That is because “fill in” means “to supply what is missing” – in the example, that would be information, but by the same token, one can “fill in” an outline to make a solid shape, and one can “fill in” for a missing person by taking his/her place. “Fill out”, on the other hand, means “to complete by supplying what is missing”, so that form we mentioned will not be filled OUT into we fill IN all the missing information.

An alarm may “go off” and it may be turned on (ie. armed), but it does not “go on”. That is because the verb “to go off” means “to become active suddenly, to trigger” (which is why bombs and guns also go off, but do not go on).

Thank you, language & history side of tumblr