Everyone makes a big deal out of Medea murdering her kids like she didn’t have the power to bring them back from the dead. She took the bodies. She knew what she was about.

In hindsight, this also applies to Media.

Tag: mythology ftw

Valhalla does not discriminate against the kind of fight you lost. Did you lose the battle with cancer? Maybe you died in a fist fight. Even facing addiction. After taking a deep drink from his flagon, Odin slams his cup down and asks for the glorious tale of your demise!

Oh my god, this is beautiful.

A small child enters Valhalla. The battle they lost was “hiding from an alcoholic father.” Odin sees the flinch when he slams the cup and refrains from doing it again. He hears the child’s pain; no glorious battle this, but one of fear and wretched survival.

He invites the child to sit with him, offers the choicest mead and instructs his men to bring a sword and shield, a bow and arrow, of the very best materials and appropriate size. “Here,” he says, “you will find no man who dares to harm you. But so you will know your own strength, and be happy all your days in Valhalla, I will teach you to use these weapons.”

The sad day comes when another child enters the hall. Odin does not slam his cup; he simply beams with pride as the first child approaches the newcomer, and holds out her bow and quiver, and says “nobody here will hurt you. Everyone will be so proud you did your best, and I’ll teach you to use these, so you always know how strong you are.”

————

A young man enters the hall. He hesitates when Odin asks his story, but at long last, it ekes out: skinheads after the Pride parade. His partner got into a building and called for help. The police took a little longer than perhaps they really needed to, and two of those selfsame skinheads are in the hospital now with broken bones that need setting, but six against one is no fair match. The fear in his face is obvious: here, among men large enough to break him in two, will he face an eternity of torment for the man he left behind?

Odin rumbles with anger. Curses the low worms who brought this man to his table, and regales him with tales of Loki so to show him his own welcome. “A day will come, my friend, when you seek to be reunited, and so you shall,” Odin tells him. “To request the aid of your comrades in battle is no shameful thing.”

———-

A woman in pink sits near the head of the table. She’s very nearly skin and bones, and has no hair. This will not last; health returns in Valhalla, and joy, and light, and merrymaking. But now her soul remembers the battle of her life, and it must heal.

Odin asks.

And asks again.

And the words pour out like poisoned water, things she couldn’t tell her husband or children. The pain of chemotherapy. The agony of a mastectomy, the pain still deeper of “we found a tumor in your lymph nodes. I’m so sorry.” And at last, the tortured question: what is left of her?

Odin raises his flagon high. “What is left of you, fair warrior queen, is a spirit bright as fire; a will as strong as any forged iron; a life as great as any sea. Your battle was hard-fought, and lost in the glory only such furor can bring, and now the pain and fight are behind you.“

In the months to come, she becomes a scop of the hall–no demotion, but simple choice. She tells the stories of the great healers, Agnes and Tanya, who fought alongside her and thousands of others, who turn from no battle in the belief that one day, one day, the war may be won; the warriors Jessie and Mabel and Jeri and Monique, still battling on; the queens and soldiers and great women of yore.

The day comes when she calls a familiar name, and another small, scarred woman, eyes sunken and dark, limbs frail, curly black hair shaved close to her head, looks up and sees her across the hall. Odin descends from his throne, a tall and foaming goblet in his hands, and stuns the hall entire into silence as he kneels before the newcomer and holds up the goblet between her small dark hands and bids her to drink.

“All-Father!” the feasting multitudes cry. “What brings great Odin, Spear-Shaker, Ancient One, Wand-Bearer, Teacher of Gods, to his knees for this lone waif?”

He waves them off with a hand.

“This woman, LaTeesha, Destroyer of Cancer, from whom the great tumors fly in fear, has fought that greatest battle,” he says, his voice rolling across the hall. “She has fought not another body, but her own; traded blows not with other limbs but with her own flesh; has allowed herself to be pierced with needles and scored with knives, taken poison into her very veins to defeat this enemy, and at long last it is time for her to put her weapons down. Do you think for a moment this fight is less glorious for being in silence, her deeds the less for having been aided by others who provided her weapons? She has a place in this great hall; indeed, the highest place.”

And the children perform feats of archery for the entertainment of all, and the women sing as the young man who still awaits his beloved plays a lute–which, after all, is not so different from the guitar he once used to break a man’s face in that great final fight.

Valhalla is a place of joy, of glory, of great feasting and merrymaking.

And it is a place for the soul and mind to heal.

I’M NOT CRYING YOU’RE CRYING

THIS IS GLORIOUS

Beautiful.

Well I AM crying and have no shame in admitting it. Absoutely beautiful!

A woman enters the hall, arms wrapped tight around her. Her hair is dirty, red rimmed eyes hollow. Her clothes are worn, her soul is shadowed and grey.

Odin asks and all she says is ‘I’m sorry.’

Odin asks again, voice low and warm like the embers of a fire.

‘I’m tired,’ the woman says.

‘Then drink and rest,’ Odin says offering up a goblet filled to the very brim.

The woman shakes her head, tears welling from some deep place echoing with the cold and salt of bitter waves. It takes time before the woman speaks of a life lived on the edge, the battle each day from morning to night, the dark thoughts that dwell within.

‘You have long fought the twin demons of Depression and Anxiety, Warrior Maiden. The darkness is all consuming, with thoughts sharp as blades, and tongues of acid to wrap around your soul. There is no shame in the help you needed, with words and healing potions. It is time to lay down your weapons, your fight is over. You have a place in this hall, to rest and heal from the demons that fed on your soul.’

These are the most beautiful things I’ve ever read.

Heroes, all of them.

It’s back. This meant everything to me the first time I read it. Still does.

Always reblog

Life advice from the goddesses

Athena says:

“My darlings, fear not the fire of change. Let it burn away the old to bring growth. It hurts, but it is necessary for new life.”

Aphrodite says:

“Dear ones, dance when you realize your self worth is in your own hands and rooted in your feet.”

Hecate says:

“Witches, do not fear the unknown. For today was the future only a moment ago.”

Artemis says:

“Hunt for who you are, in the deepest parts of your ribs. This is holy.”

Hera says:

“Children, make mistakes and come to terms with them. Learning comes with sacrifice.”

Persephone says:

“choice is a fickle thing and many will attempt to rewrite your story. Be who you are, choose yourself. Change only when the growth is good for you.”

Hestia says:

“Babies, may you light your hearth where your chosen family lies, and do not believe the falsehood that you are trapped by blood.”

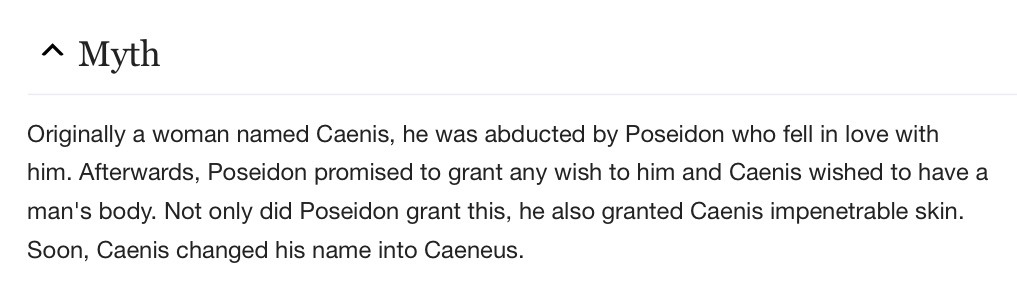

shout out to my fave under-appreciated unbreakable transgender hero

The thing that gets me is he didn’t ASK for the impenetrable skin. Poseidon was just like “cool cool but you know what you need? skin of IRON. don’t worry bud it’s on the house”

I just love the myth of Persephone, i mean the real, original version of it, because it’s not like she got kidnapped, no, this bitch was la-de-da-ing in a meadow and she just happened to find an entrance to the Underworld and she was like “Imma check this out”. And she just wanders into the Underworld and discovers that hey this place ain’t too bad.

Meanwhile Hades is in the background “????? UM??? PRETTY GIRL??? WHY ARE YOU HERE?????? YOU AREN’T DEAD???”

And Persephone (who was originally called Kore just a little fyi) just looked at him and said “I like it here. I’m staying.”

And Hades kinda just went with it, until Demeter started throwing the temper tantrum of the millenium upstairs and Zeus had to intervene because this shit was getting out of hand and its actually his job to be admistrator of justice. Which considering the shit he gets up to is kinda histerical but that’s another story there.

And basically Persephone wasn’t a prisoner or kidnap victim at all she just really loved the Underworld and her (eventual) husband, and the Greeks feared her arguably more than her husband because Hades could be reasoned with but Persephone was the one laying the smack down on sinners, and really, who wouldn’t be at least a little scared of someone who’s name means something along the lines of “the destroyer”

Basically, Persephone is amazing and everbody needs to get on her level

@teashoesandhair, is this true and right and accurate? I ask you because you are The Knowing when it comes to things of this nature…

*sweats nervously* no, this is not true and right and accurate.

(Edit 2: tbh any post that says THIS IS THE ORIGINAL MYTH is going to be wank, because we don’t know what the original myth was – we only have the first written sources, but without a time machine there’s just no way of finding out how the myth developed in an oral tradition)

The first source we have for Persephone being carried away is in Hesiod’s Theogony, written in the 8th or 7th century BC. We also have the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, written in the 7th or 6th century BC, which is explicitly about her being taken away by Hades.

Hesiod is one of the oldest Greek sources that we have, roughly contemporaneous with Homer. We don’t have any earlier sources than this which say ‘hey, Persephone went to Hades because she thought it would be cool’. A lot of people have theorised that this could have been an original, or at least an earlier tradition, but it’s about 60% wishful thinking, 20% misinterpreting evidence (i.e. assuming that Persephone and Demeter used to be aspects of a great mother goddess, which they weren’t) and about 20% conjecture based on actual rational thought (i.e. the fact that the oldest written source we have is about an abduction doesn’t mean that it is the original source; there could be older non-extant written sources or just oral tales which pre-dated writing). It’s not fact.

It’s true that Homer himself never explicitly says that Persephone was abducted (he just describes her as Hades’ wife) but he also doesn’t say that she wasn’t abducted; it could well be that the myth of her abduction was so well known that he had no need to recount it.

It is true that Persephone’s name was Kore, which means ‘maiden’; however, this could be an epithet because she was unmarried. (Edit 3: it’s also theorised that it was a euphemism of sorts for when people didn’t want to name Persephone outright; again, this is a theory). The name ‘Persephone’ does not mean death / destroyer; the etymology is unknown (the ‘death / destroyer’ theory is just one of many, and others are based around ideas of harvest and grain).

The reason Zeus got involved wasn’t just because he was tasked with sorting out justice – it was because he had told Hades ‘hey, you want a wife? Cool! Abduct my daughter, Persephone. Her mum totally won’t mind,’ and then when Persephone’s mother did mind, Zeus was like ‘I fucked up real bad, I should sort this shit out.’ Edit 4 – in Ancient Greece, women didn’t have to consent in the same way as we do now. Abduction marriages were actually illegal (or at least very very naughty) but the bride’s consent basically took the form of her father saying ‘you’ll marry this dude, right? Yeah, cool. She’ll marry you, dude.’ Here, Zeus gives Persephone’s consent to Hades by telling Hades that he can marry her – this is why technically she wasn’t exactly abducted, because the necessary consent – her father’s – was given. HOWEVER, let’s not get into Greek law here. She was abducted by our standards.

It is also true that Persephone became a very feared goddess and basically had a great time in the Underworld. She wasn’t exactly more terrible than Hades, though; there are certain myths (e.g. Sisyphus and Orpheus) where she’s the one who says ‘Hades, babe, shall we give this guy a chance to make his way out of the Underworld alive?’ HOWEVER, she did usually do this with the implementation of specific terms, meaning that she had a level of control in proceedings which a lot of other wife goddesses didn’t have over their respective spouses’ spheres. Most mythological canons also give her and Hades a very healthy and monogamous relationship (with the exception of Orphism, which is a bit more iffy on that front) so, disregarding the abduction part of her myth, their marriage was really relatively healthy, even by modern standards. (Edit 5: also, Persephone did not ‘lay the smack down on sinners’ – the whole idea of sinners is basically a Christian concept. The Underworld was not Hell. It wasn’t a place for bad people. It was just where the dead went. Tartarus was the place where the really bad guys went to be tortured and shit, and is more indicative of Christian notions of Hell. People weren’t punished in the Underworld. They just went there.)

I love the idea of Persephone as a consenting wife of Hades. I am a fan of modern reinterpretations in which she chooses to eat the pomegranate seeds willingly, or where she falls in love with Hades and goes to the Underworld of her own accord. However, these are modern interpretations, based on modern gender politics and ideas of reclamation and representation. I will forever fight for people’s right to reinterpret myths however they like, but this whole idea of the ‘original myth’ of Persephone being devoid of any misogynistic undertones really needs to die.

(Edit 1: putting my tags here in case anyone thinks I’m just a hideous puritan:

#i love all the myriad interpretations where she actually has agency #but she didn’t in any of the oldest original sources that we currently have #and i don’t like people saying that she did #because it negates all the misogynistic bullshit that women have been subjected to #and i don’t think it should be negated

I should also point out that I’m doing my MA dissertation partly on the modern feminist reclamation of patriarchal myths, including the erroneous claims that these myths were originally matriarchal, so this post definitely counts as work and I’m 100% not procrastinating… sort of…)

Every time I see this post without @teashoesandhair’s contribution I feel compelled to hunt it down again

KLYTAIMNESTRA : And why get angry at Helen?

As if she singlehandedly destroyed those

multitude of men.

As if she all alone

made this wound in us.

what if medusa was a real woman. i mean: what if the woman with snakes in her hair was once a tiny girl with beautiful braids in her black hair.

what if the stories came from her smooth hands. when she was six she could make pottery that looked like flowers blooming in your palms. could carefully create replicas of any plant she saw.

and medusa was smart. ran from home, tucked up her hair so it looked short, made herself into a little boy. besides, they liked pretty boys. medusa at school with top grades, sending her unknowable stares at the other men. because the whole time she’s learning the planes of their faces, the way they look while they’re thinking, the slight twist of their hand that meant they were lying.

medusa going home to sketch every little figure. comes to school in the morning with her hands caked in pottery clay. medusa learns. scrubs dirt on her face to mimic their planes. tilts her head the right way when she’s thinking. doesn’t twist her hand when she’s lying.

in her back yard, a little garden grows. statues of ceramic boys only three feet tall. at first, she can’t quite get the faces right. men are not the same as plants. there is something weird about the proportions she uses. medusa frowns.

she starts making animals instead for a bit, annoyed and disheartened. she’d always just been naturally good at it, and the fact she couldn’t just make something felt as if she’d lost her gift.

she makes cats and dogs and her neighbor’s birds and keeps going.

the snake wasn’t her favorite. he just wouldn’t leave her alone, so she gave up and let him sleep on her in the cold nights. besides, he was a small garden snake, couldn’t even bite her hard, just wanted a place of warmth. she let him rest on the angles of her shoulders, right near her neck, even if he sometimes forgot and held her too hard. that was okay. when she was little, she forgot too, sometimes, and shattered the slim walls of her pottery. the snake had a lot of growing up to do.

she loved no one. not because she was cold-hearted. just because it wasn’t something she wanted. she was busy with her artwork.

she chose an apprenticeship under a master craftsman. his sculptures made her breath stop. she was careful in the workshop, kept her things simple, kept her mouth shut. he called her stupid often. she would duck her head. sometimes she would make mistakes on purpose. all the while he only made sculptures of men. said there was no beauty in women. often made savage remarks about those they saw in the market.

and all the while, she watched him. she watched him and she went home and sketched. this is how his hands were when he made a vine. this is how they were when shaping a nose.

and her back yard garden would grow. little boys became her master, over and over and over, until she could get his jaw right. ceramic became sculpture.

he was who took her to athena’s temple. who shouted at her about how beautiful the statues were against her own. every week he’d come back and shame her. asked how the women there were smarter than the man she was supposed to be. medusa ducked her head and grit her teeth.

in her back yard, she made them. she made every god and goddess she’d seen in the city. her favorite was athena. she ached over her features. had spent so long in the world of men, was blinded by the beauty of women.

it was a black night. and medusa thought her master had left the temple before her. she loosened all the bindings that kept her from breathing. took her hair out. worshiped in peace. placed on athena’s alter a small and beautiful thing. the goddess, head tilted, thinking.

when he found medusa, what made him angry was not her small frame. it was the statute. a delicate thing. much better than the ones he had ever made.

he took it and snapped it in half. threw it deep in the temple’s well to rot. pulled her by her hair. demanded to know where it had come from.

medusa, angry, tired of hiding, tired of late nights and being a boy and pretending: medusa, athena-mad, spat on him. “I did it,” her voice is strong and full of hatred, “A woman made something better than a man could.”

He meant to kill her. To bash her head into the temple steps, claim it was an accident – or better yet, the spite of a god made flesh.

when he grabs her hair, the goddess bites back. athena, patron of creators, patron of the arts, patron of girls and those who are smart – she turns medusa’s hair into snakes.

it is a quick little thing, darts out and draws blood, almost falls from her hair as a result. she catches the creature and runs, runs until she feels numb.

and what if – while her master is explaining her back yard full of frozen men as being evidence of her evilness – what if medusa finds friends in blind women. and they teach her how to feel what she is seeing. how to use her hands with her eyes closed to make maps of whatever she holds. she starts with plants again. her snake is big now, and has babies. she moves on to their little wiggling forms, amused when they make tiny rings around her fingers. she does not live in a cave. she dresses as a man again, goes to market, sells her roses and vines and beautiful (simple) things. buys herself and the women a nice house out beyond all the noise of it. fills their garden with frozen men.

when the men come to kill her – because now her name is known, it is whispered, sticks in the throat – they don’t find her. they find a tall man who tells them: look in the mountains. when they don’t come back, it’s no fault of medusa’s. frankly, she thinks they should have brought more supplies than their swords into the deep woods. she’s not cruel. when they leave, she makes a statue of them, as her version of a memorial.

but one man is not like the others. he finds her with her hair down, humming, dancing around a marble stone. her snakes are warming in the sun.

medusa? he asks her. it’s a name she hasn’t heard in a long while.

she is tired of being hunted. she just wants to make art. she waits for the sword point. but he hesitates. looks at her full in her face.

strikes a bargain. if she makes him a head for his shield, he will tell the others that she is good and dead. and he will sell her art to better patrons when he could – although he suggests at least hiding the signature she has with maybe a little less snake-like scrawl – he would make her name known.

but medusa knows men. knows they will chomp down on a horror story faster than that of the artist. she is already permanent. she says: no, here’s what happens.

after many months, he has his shield. she wouldn’t let him leave with the first nine hundred versions, always found something wrong with them. he grows fond of her in this time, agrees to her terms. even he can’t really look at the shield head-on. she has captured a scream, a rage, too much. it is so utterly human and at once not that it makes his skin crawl.

where medusa’s blood drops, serpents sprawl. or at least, that’s the code she uses. when he finds little girls who can make art, he sends them to her.

medusa does not expect to be known for the school that she starts. she is a women artist in a time of men, and her name is already dead to them. but i know medusa. i know her. she is known for her work.

after all, who can speak about medusa without mentioning how she froze the world?

Love love love this.

A cat makes its way through the corridor of the Girdle Wall of the Temple of Horus at Behdet.

or – Bastet pays Horus a visit.

For some reason the sum total of the amount of time that has passed since these walls were built really hits me in this picture.

The story of Cassandra, the woman who told the truth but was not believed, is not nearly as embedded in our culture as that of the Boy Who Cried Wolf—that is, the boy who was believed the first few times he told the same lie. Perhaps it should be.

The story of Cassandra, the woman who told the truth but was not believed, is not nearly as embedded in our culture as that of the Boy Who Cried Wolf—that is, the boy who was believed the first few times he told the same lie. Perhaps it should be.